Folds in Fashion: the Art of Pleating in Clothing Design and Construction

"Making dress is all about how to relate flat fabric to a three-dimensional figure in the class of the human body. European-style couture involves giving three-dimensional class to material past using curved lines and darts to fit it to the body… The kimono, in dissimilarity to the construction of Western vesture, is an assemblage of rectangular pieces of textile… Examples of this approach... include simply draping a piece of apartment fabric over the body, as in Issey Miyake's 'A Piece of Cloth' concept in 1976." So Akiko Fukai argues in Future Beauty: thirty Years of Japanese Fashion. Since the publication of Anne Hollander's Seeing Through Dress, the assertion that kimono resembles a flat canvass when compared to the sculptural Western apparel, has been rather prevalent. As a result, the works of modern-day Japanese designers such equally Issey Miyake are too likened to a flat sheet, characterized by what seems to be the "lack of intervention with fabrics."

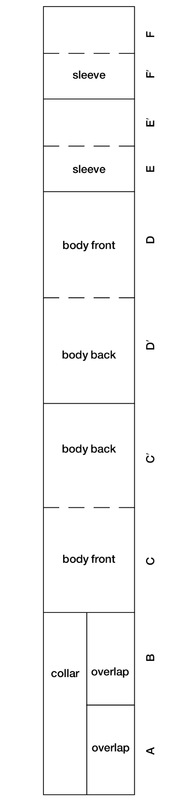

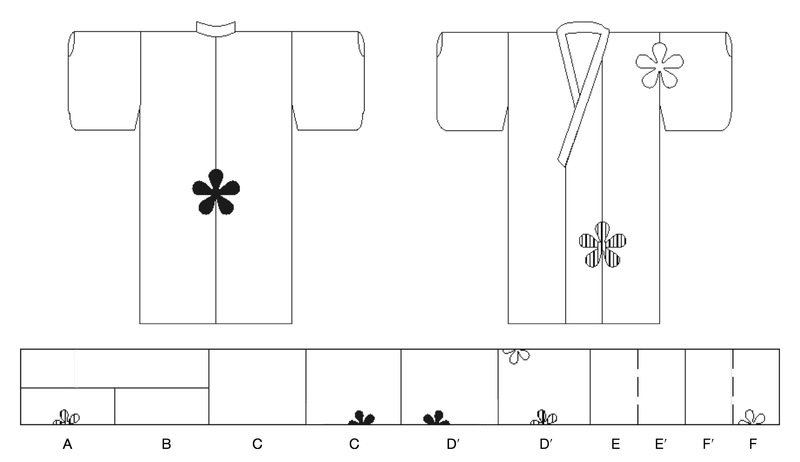

Kimono, with its geometric outline and standard size, tin can easily exist perceived as a apartment garment. However, every bit Aarti Kawlra brilliantly showcases in her essay, "The Kimono Body," kimono is constructed flatness. That says, the making of a kimono pivots around the premeditation over textiles, rather than the tailoring tradition. In making a kimono, it is fabric artist who delineates the various trunk parts, past weaving, dyeing, painting and printing. Every bit shown in the figure on the left, the design of each trunk section must be composed of mirror opposites, whose apexes meet at the shoulder mark - the dotted line. If the order is non adhered to, patterns would appear upside down. Fifty-fifty and so, weaving or dyeing with the alternating blueprint upside downward is preferred to cut and seaming the fabrics.

Kawlra's demonstration is specially pregnant because, for the study of a kimono, she takes on a material approach, despite or precisely because of the authority of semiotic readings within academia. Indeed, information technology is important to recognize textiles and dress equally social and psychological phenomena. But it is just as of import to sympathise the fabric in its ain right. An examination of the kimono's construction not just reveals data previously neglected in the study of the garment every bit a cultural product, but also points to other non-tailored garments such as sari, sarong, and shawl. As Susanne Küchler rightly concludes: "We accept not even so even begun to realize the full implication of the dawning of a material arroyo to thinking and knowing, still we sense that it will certainly revolutionize the fashion we have regarded what appeared as but decorative and ornamental." It is my intention, then, to combine both the fabric and the cultural approaches upon the study of Issey Miyake'southward blueprint.

As a mode designer, Issey Miyake has heavily invested in textile experiments. He established his design studio in 1970 equally a laboratory for enquiry on fabric applied science and design techniques. While his works are remarkable for their aesthetics, his abiding interest in textile manipulation and metamorphosis proves to be the central to his success. Similar a kimono maker, Miyake designs clothes by making the cloth.

A-POC

Amongst his almost acclaimed projects is A-POC, initiated in 1997, led past Issey Miyake and engineering designer Dai Fujiwara. Its proper name is an acronym for "A Piece of Fabric" and refers to the idea of "epoch." A-POC entails a manufacturing method that uses reckoner engineering to create clothing from a single slice of thread in a single process. The method provides a solution to an array of challenges, including those of product, wearability and portability. In the very first incarnation of A-POC, tubes of double-knit textile, with yarns linked in a fine mesh of chain stitches, were produced on a reformed Raschel knitting motorcar, made without seams, finished on a gyre. The garments stitched within the tube are to be cutting free by the wearer. Once the garments are cut costless, the bottom layer of mesh will shrink, keeping the cloth from unravelling. By formulating the fabrics, Miyake designs vesture without seaming and tailoring.

The beginning results of the project, including "A-POC Male monarch & Queen, A-POC Le Feu," were presented in the Spring/Summer 1999 ISSEY MIYAKE Paris Drove. Post-obit that, PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE and other collections began to develop items based upon the A-POC method starting in 2003. After 2007, the collection introduced blueprint solutions under the subtext of "A-POC INSIDE" and has continued to refine its vision for making garments.

PLEATS Delight

PLEATS PLEASE was introduced into ISSEY MIYAKE in 1989, when the designer presented a series of functional garments made from pleated polyester, refined and released to commercial production every bit the "Pleats Please" line in 1993. Miyake's interest in new textiles, such as polyester, is related to his environment. Japan has over the centuries developed a sophisticated material industry and, since World War II, has focused on the regeneration of its manufacture manufacture. Although Miyake relied on his extensive studies of the traditional Japanese sartorial techniques to create clothes with contemporary appearances, he too worked with Japanese synthetic-fibre manufacturers. In the 2nd half of the 1980s, these new synthetic' fabrics made from polyester were attracting worldwide attention.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s Miyake developed and refined his revolutionary pleating technique, in which polyester is cut into the shape of a garment and then heat-pressed to create permanent pleats. The PLEATS PLEASE line, decorated with bright colors and abstruse geometric patterns, is not but light in weight but also machine-washable. Fantastically rational, internationally viable, this is a line positioned to embody 1 of the virtually central concepts of Issey Miyake - the true value of design lies in its integration into the everyday life. Miyake himself explains: "My offset dream, and why I first decided to open my studio, was that I thought: 'If I could one twenty-four hour period make wearing apparel like T-shirts and jeans, I would be very excited.' But I was e'er doing such heavy things far away from the people. And then I was thinking, y'all know, 'Are you stupid? Don't you call up why you started designing in the first place?' And and then I thought, 'Okay, Pleats Please.' So I started to think how to make information technology, how to wash it how to coordinate it, even how to pack information technology. And I worked on how to go on the price down." Miyake does not deem couture or theatrical extravaganza equally the culmination of fashion design. Rather, he designs in response to the everyday problems and needs in people's lives, almost treating fashion design every bit industrial blueprint.

HOMME PLISSÉ

HOMME PLISSÉ is another habiliment concept fabricated possible by the continuing development of Miyake'southward original pleating technology. The line has not only called the wrinkle-resistant and quick-drying fabrics, but too uses compatible pleats in social club to forestall the garments from clinging to the peel. In addition to the PLEATS PLEASE pleating process, whereby the pleating takes place later on the cutting and sewing, some products are sewn later the fabric is pleated.

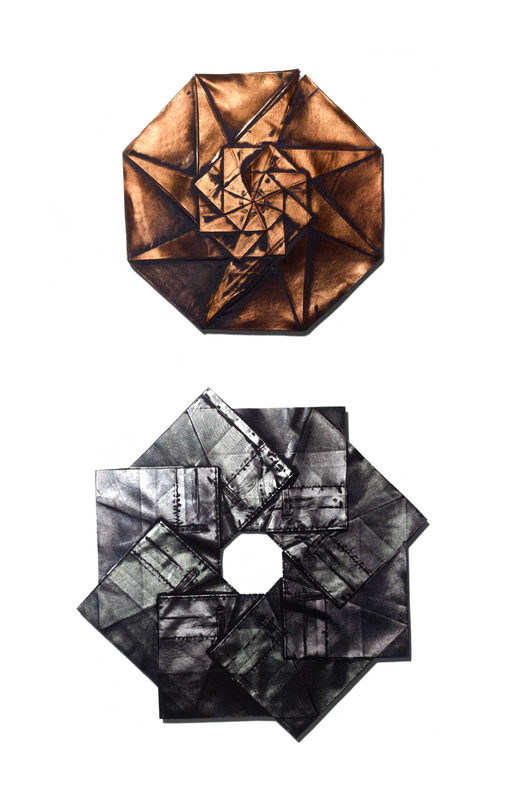

132 5.

132 5. adult past Issey Miyake and his Reality Lab. team, is another reincarnation of A-POC. The process by which the vesture is made, originally inspired by origami, is groundbreaking. First, a diversity of 3-dimensional shapes are conceived in collaboration with a computer scientist; then, these shapes are folded into ii dimensional forms with pre-ready cutting lines that determine their finished shape; and finally, they are heat-pressed, to yield folded shirts, skirts, dresses etc. Over again, the fabrics are not undifferentiated yardages. The wearing apparel are precisely embedded within the fabrics. Aside from that, these garments are made with recycled fibers.

IN-EI

As a continuation of 132 5., IN-EI is a collection of lights created by Issey Miyake + Reality Lab., manufactured by Artemide. For the lampshades, the non-woven fabric made from recycled PET bottles is used, with special surface handling. The lights require no internal frame to back up themselves, and can be folded flat when non in use, just equally the garments from 132 5.. For Miyake, the logic of manner design resonates with that of the industrial blueprint.

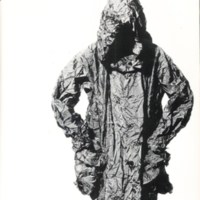

Innovations as such have earned Miyake a proper name in the fine art world as well. Large-scale exhibitions of his designs take traveled effectually the earth, showcasing their sculptural beauty derived from constructed flatness.

0 Response to "Folds in Fashion: the Art of Pleating in Clothing Design and Construction"

Post a Comment